Flying in the face of complacency

Bangkok Post, January 25, 2007

AMITHA AMRANAND

Manit Sriwanichpoom has a real gift for finding the political in the prosaic, the brilliant in the apparently banal, and his latest collection of photos displays a further sharpening of his vision

|

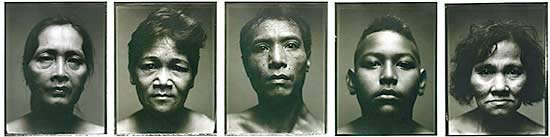

| Some of the faces of Bangkok as seen through the lens of Manit Sriwanichpoom. |

Our capital teems with faces, millions of faces - old, young, strange, familiar, native, foreign, tortured, pensive, inscrutable, elated - but how many of them fade into anonymity, swallowed up by the congestion and the frantic pace of urban life? Through his photographs, Manit Sriwanichpoom has transformed voices drowned out by the crowd into articulate cries for help, driven forgotten images back into contemporary consciousness and pushed obsessions to their grotesque limits. Most recently, he's turned numbers into names, bringing a handful of faces into sharper focus.

More familiar than strangers, yet individuals with whom Manit is barely acquainted, the 60 people featured in his new exhibition, "Ordinary/Extraordinary", live around the photographer's studio on Soi Onnuj, a once-idyllic part of Bangkok. Its 20-plus kilometres are now lined with housing estates and apartment buildings, inhabited by people from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds.

|

| `Ordinary/Extraordinary' opened yesterday at Tang Contemporary Art, Silom Galleria where it will continue until February 20. |

"It's like looking at a map of Bangkok through a magnifying glass, focusing on one little section of the city," Manit said. "Usually, we just walk past these people without really looking at their faces. And they themselves don't think their faces are interesting because there are plenty of 'interesting' faces in the pages of newspapers and on TV."

Taken at an intimate range with simple lighting and without direction or posing, each photograph exposes a visage as revealing and as complicated as a map. These are the faces of the working class, but also of children, of men and women of all ages and sexual orientations, from an array of occupations and birthplaces. And even though most of his subjects aren't natives of Bangkok, to Manit their faces tell the stories of the city - of economic migration and how diverse a tiny corner of this metropolis has become.

"Can we see something within a face? Can it be like a story - a short story about someone? These photographs can be like a documentary, an anthropological or sociological study of a society that is made up of people of many backgrounds. And if you just look at them, each face has its own intrinsic beauty. There's life. There's birth, old age, sickness and death in all of them."

Wanting to study architecture in college, but failing to score enough points to qualify for the programme, Manit ended up majoring in visual arts at Srinakarinwirote Prasarnmit University. His dream of becoming an architect was to prove short-lived, however.

"The first time I laid hold of a camera - seriously picked up a camera - I felt it was part of my body. It's kind of like when a painter touches a paintbrush for the first time and can sense that this is how he should express himself."

It was the work of veteran lensman Pramual Burutsapat that introduced Manit to the world of art photography, opening his eyes to the vast potential of this genre. At that time, the early 1980s, more and more of his compatriots were searching for new ways to take pictures, experimenting with different methods of capturing images on film.

"It was no longer just about having a camera and going out into the streets to take pictures," he recalled. "The work of Acharn Pramual paid attention to the form, the resulting image and the visual effect created. It experimented with putting images together to create a new image. That was what got me interested. I was used to doing straight photography - what you saw in front of the lens was what you got in the photograph. What I didn't know was that you could create a whole new form or image with photography. So it was like love at first sight."

Looking back now at his earlier work, Manit can't help but be amused at the level of self-absorption involved. Not that he's embarrassed by his youthful indulgences and romantic explorations; he just sees them as another stage in his artistic development. If he hadn't gone through that phase, he said, he wouldn't have become what he is today. But the politics that would later inform the better known portion of his oeuvre was already germinating within, the seeds sown back when he was a teenager in the '70s, enthralled and inspired by the fiery university students of the day.

"I was influenced by the people involved in the October 14, 1973 and October 6, 1976 student uprisings. I was 15 when October 6 took place. And, later, when I entered college myself, some of the students who had fled to the jungle had just begun to return. For people my age, these men and women were our heroes. They had dreams. They wanted to better society. They wanted to see equality. These were the great things that the October generation instilled in people of my age. I saw their ideals as a legacy that we needed to uphold and carry forward. So I began to question my own role as well."

Before getting into conceptual photography, Manit made a detour into advertising. And the self-discipline he had to acquire for this job continues to influence his working style to this day. He went on to work as a cameraman on a series of documentaries for local TV before becoming a photojournalist, originally with a local publication and later freelance. While photojournalism widened Manit's horizons, the professional necessity to remain objective at all times made him itch to make statements about what he saw passing in front of his lens.

"I had a background in art and with art I could express my views, but as a photojournalist I couldn't express my opinions. I had to carry out assignments - waiting for phone calls, for something to happen. But I had opinions about politics and society. I felt that I had something to say. I think that the media can do a lot for society - like revealing the truth of a matter to the general public, but that wasn't for me. When you work for the Press, you have to keep your opinions to yourself. You have to be careful. And that felt very limiting to me."

Much of his best-known work comprises critiques of the economic system that dictates our daily existence. He often depicts the impacts of globalisation and consumerism with devastating humanity. For "The Bloodless War" (1997), Manit based his photos on familiar images of the Vietnam War, replacing civilian casualties and soldiers with shoppers and men in business suits to convey the idea that imperialism hasn't disappeared, but has merely changed form. He then took these photographs to the streets of the financial district and to places like the SEC that represent the new economic reality, and hung them from the necks of friends of his who then stood around wearing stoic expressions - like so many silent protesters.

Three years later, he chronicled the casualties of Thailand's stock-market crash in mid-1997 in his "Dream Interruptus". Unfinished high-rise buildings stand like the detritus of a violent war in this bleak series of black-and-white photos.

Manit's photography, whether satirical, protest or documentary, reveals a sensitivity toward, and a sharp perception of, urban conflicts and decadence. In his "Protests" series, where the influence of his days as a photojournalist is most apparent, he chronicled the sit-ins by indebted farmers, anti-dam activists and other disgruntled groups that took place every Tuesday in front of Government House for the best part of a year. These images expose how the problems besetting rural people have bled into urban consciousness and reflect the uneven distribution of power and the dysfunctional nature of the Kingdom's brand of democracy. "Protests" also throw the question back into the ring as to the proper function of photojournalism; for Manit believes that images like these belong in the public domain - on the pages of newspapers rather than on the walls of art gallery.

But his social criticism is not all dark, not all raging. His best-known creation, a piece of performance art he dubbed Pink Man, looks at the world through a consumerist mindset, dripping with mordant, deadpan humour. Created in early 1997, just two months before the onset of the economic slump, the character of the Pink Man - embodied by Sompong Thawee who, in his first incarnation, dressed up in a shocking-pink suit to wheel a pink supermarket trolley down Silom Road - has outlived the lifespan he originally intended for it, a series of three performance/photographic happenings.

"I found that the character took on a life of its own - one of the reasons being the audience response to it. And, as an art piece, it can continue because it is still making social commentary. It's like a cartoon character, like Batman or something. When some trouble crops up, he comes to the rescue. In the case of Pink Man, he has become a reflection of current events in our society. I see the character as reflecting an entire era."

Pink Man has journeyed from commenting on consumer habits and globalisation to wandering around deserted tourist spots in Bali after the 2002 nightclub bombings as a lost, powerless figure, to posing with naked French women in Paris, evoking Manet's portraits of nudes, as a statement on Asia's rising power and ego.

Not so well known is the fact that he took a campaign photo of Thaksin Shinawatra, during the brief period that the latter was leader of the Palang Dharma Party. Manit revealed that a few people later blamed him for aiding Thaksin's rise to power. He, however, wouldn't go so far.

"At that time, everyone had great hopes for Thaksin. He was different from the old breed of politician that Thai people were sick of. Nobody, including myself, knew back then what he was really like. And I don't dare claim that the picture I took got him to where he was. I think that would be giving myself too much credit. What I did was give that man a chance. That was my duty then. When I realised what he was really like, I continued to do my duty as a citizen by speaking out against him."

And to Manit, his duty as an artist - and as an individual - is to try to understand others. He is among the 55 photographers from Thailand and abroad who has been chosen to take part in Thailand: Nine Days in the Kingdom, an ambitious, illustrated-book project to honour HM the King on the occasion of his 80th birthday later this year.

And strangely, for someone better known for his images of the working class, this soft-spoken photo-artist is soon to embark on an exploration of one of Bangkok's highest-profile subcultures: The socialites who comprise the so-called "hi so" (high society) set. But no, he's not going to satirise them.

"I think it's an interesting subculture because it's a modern phenomenon. I'm interested in finding out how the media defines them and what they understand about themselves. I think there's a reason for this phenomenon and that the question that needs to be asked is, how did it arise?

"I'm not here to judge them or to say that this is a terrible thing. These people are already the target of criticism - practically on a daily basis. But we never ask why they're subjected to so much criticism. I think every single person has his or her own reason. Our duty is to understand them.

"We have to look at the world with compassion. We have to look at people with compassion."